Stephen Kurczy is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Economist, The Christian Science Monitor, and Vice, among other outlets.

He graduated from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, where he was a 2016–2017 Knight-Bagehot Fellow in Economics and Business Journalism. Kurczy has lived without a cell phone for more than a decade.

You can follow Stephen Kurczy on Twitter.

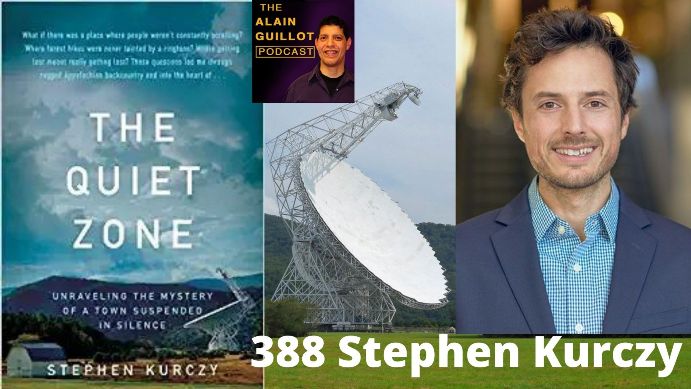

The Quiet Zone: Unraveling the Mystery of a Town Suspended in Silence

Deep in the Appalachian Mountains lies the last truly quiet town in America. Green Bank, West Virginia, is a place at once futuristic and old-fashioned: It’s home to the Green Bank Observatory, where astronomers search the depths of the universe using the latest technology, while schoolchildren go without WiFi or iPad.

With a ban on all devices emanating radio frequencies that might interfere with the observatory’s telescopes, Quiet Zone residents live a life free from constant digital connectivity. But a community that on the surface seems idyllic is a place of contradictions, where the provincial meets the seemingly supernatural, and quiet can serve as a cover for something darker.

Stephen Kurczy embedded in Green Bank, making the residents of this small Appalachian village his neighbors. He shopped at the town’s general store, attended church services, went target shooting with a seven-year-old, square-danced with the locals, sampled the local moonshine. In The Quiet Zone, he introduces us to an unforgettable cast of characters.

There is a tech buster patrolling the area for illegal radio waves; “electrosensitives” who claim that WiFi is deadly; a sheriff’s department with a string of unsolved murder cases dating back decades; a camp of neo-Nazis plotting their resurgence from a nearby mountain hollow. Amongst them, all are ordinary citizens seeking a simpler way of living. Kurczy asks: Is a less connected life desirable? Is it even possible?

The Quiet Zone is a remarkable work of investigative journalism—at once a stirring ode to a place, a tautly-wound tale of mystery, and a clarion call to reexamine the role technology plays in our lives.

A small town cut off from modern technology finds the peace of mind we’re all missing. That’s the promise in the headline “No Cell Signal, No Wi-Fi, No Problem. Growing Up Inside America’s ‘Quiet Zone’,” which appeared in The New York Times in March of last year.

According to Stephen Kurczy’s new book, “The Quiet Zone,” the reality is much more complicated.

Wi-Fi, cellphones and even some electric blankets are banned in a government-mandated area around Green Bank, W.Va. The secluded town is home to the world’s largest steerable telescope, legally protected since 1958. In theory, the 13,000 square miles surrounding the telescope are supposed to be free of any radio intereference. In practice, Kurczy discovered, nearly everyone finds a way around this obstacle.

As Kurczy writes, “Of course, most residents did have cellphones, Wi-Fi, microwave ovens and myriad other gadgets.” According to him, the claim in the Times article that Green Bank was a place “where Wi-Fi is both unavailable and banned and where cellphone signals are nonexistent” was “news to everyone around Green Bank.”

Kurczy’s book is a study in motivated reasoning. Local officials pretend to enforce laws they know almost everyone breaks. Meanwhile the press, desperate to tell stories outsiders want to hear, offers accounts that one resident called “disconnectivity porn.”

The pretense appeals to newcomers, who flock to the area to escape problems they blame on modern technology. But once they arrive, it’s clear their issues are personal rather than technological.

Originally, Kurczy himself seeks to break free: “Coming here was something of a pilgrimage. I hadn’t owned a cellphone in nearly a decade, even as everyone around me increasingly did.” Kurczy goes looking for a place where he might fit in without having to explain himself or upgrade his devices. During his stay, he meets other people stuck in their ways.

Kurczy profiles “electrosensitives,” people who “described feeling ill when exposed to iPhones and smart meters, refrigerators and microwaves.” Despite a preponderance of evidence Kurczy presents showing it’s likely not the electromagnetic forces causing their suffering, the electrosensitives demand that libraries and community centers remove light bulbs and other equipment they say causes them harm.

He also interviews neo-Nazis, who live in the isolated region to escape the race mixing they find intolerable. With their membership aging and their rosters dwindling, the white supremacists are stuck on a vision they have of the past. They isolate themselves because they are unwilling or unable to adapt. “In essence,” Kurczy writes, these people “felt allergic to modern life.”

The extremes offer a lesson. The most memorable characters in “The Quiet Zone” pathetically search for peace in a physical place. Whether it’s an escape from social media, electromagnetic waves, or people of color, they are never at ease because their torment comes from inside them — the one place they’re unwilling to look. It’s the “fallacy of elsewhere,” according to Jaynell Graham, the editor in chief of the local Pocahontas Times.

“The Quiet Zone” offers a sober portrait of people stumbling their way into an uncertain future. Readers looking to confirm their conviction that disconnecting is a cure-all will be disappointed. Those needing a reminder of the simple pleasure of reconnecting with real people in real life will enjoy the journey.

While it’s easy to decry our gadgets, given how annoying and distracting they can be, “The Quiet Zone” reminds us that our devices are just tools, and tools can be used, misused, and abused. We don’t need to decamp to a federally mandated quiet zone to ease our minds. Nor should we use our phones as digital pacifiers to reflexively escape every pang of boredom or loneliness. We can always find a quiet zone when we need it if we’re willing to take the time to do so.