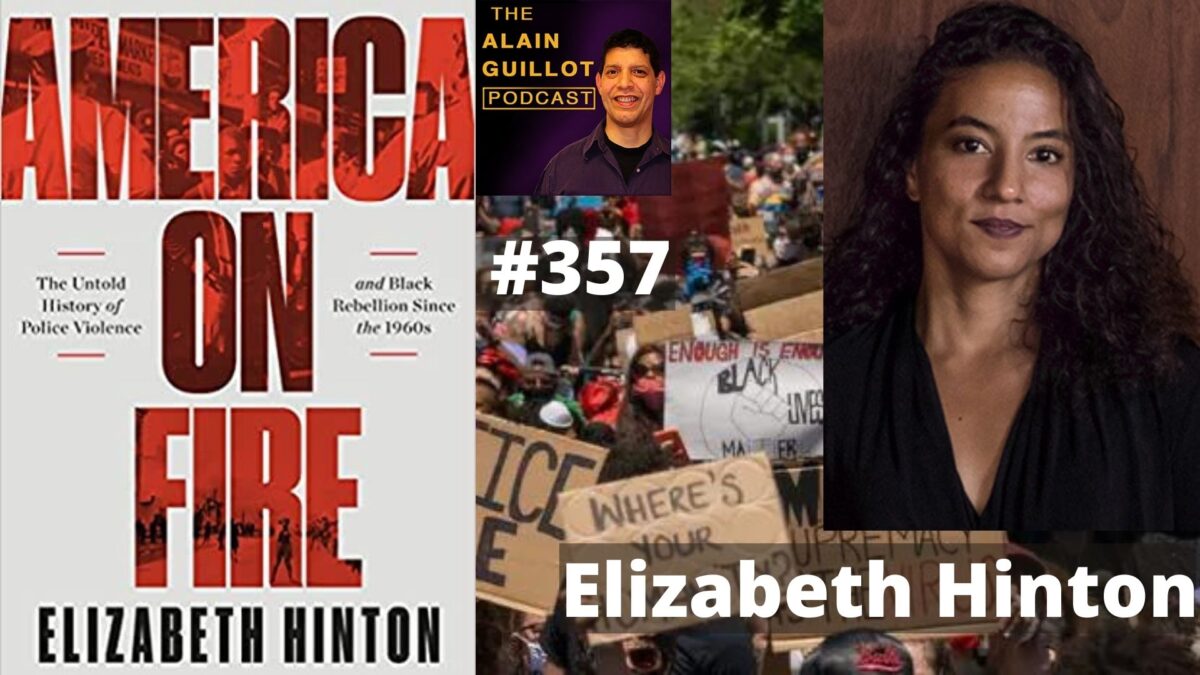

About Elizabeth Hinton

Elizabeth Hinton is an Associate Professor in the Department of History and the Department of African American Studies at Yale, with a secondary appointment as Professor of Law at the Law School.

Hinton’s research focuses on the persistence of poverty, racial inequality, and urban violence in the 20th century United States. She is considered one of the nation’s leading experts on criminalization and policing.

In her book From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Harvard University Press), Hinton examines the implementation of federal law enforcement programs beginning in the mid-1960s that transformed domestic social policies and laid the groundwork for the expansion of the U.S. prison system. In revealing the links between the rise of the American carceral state and earlier anti-poverty programs, Hinton presents Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs not as a sharp policy departure but rather as the full realization of a shift towards surveillance and confinement that began during the Johnson administration.

Before joining the Yale faculty, Hinton was a Professor in the Department History and the Department of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. She spent two years as a Postdoctoral Scholar in the Michigan Society of Fellows and Assistant Professor in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan. A Ford Foundation and Carnegie Corporation Fellow, Hinton completed her Ph.D. in United States History from Columbia University in 2013.

Hinton’s articles and op-eds can be found in the pages of the Journal of American History, the Journal of Urban History, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Boston Review, The Nation, and Time. She also co-edited The New Black History: Revisiting the Second Reconstruction (Palgrave Macmillan) with the late historian Manning Marable.

America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s

What began in spring 2020 as local protests in response to the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police quickly exploded into a massive nationwide movement. Millions of mostly young people defiantly flooded into the nation’s streets, demanding an end to police brutality and to the broader, systemic repression of Black people and other people of color. To many observers, the protests appeared to be without precedent in their scale and persistence.

Yet, as the acclaimed historian Elizabeth Hinton demonstrates in America on Fire, the events of 2020 had clear precursors―and any attempt to understand our current crisis requires a reckoning with the recent past.

Even in the aftermath of Donald Trump, many Americans consider the decades since the civil rights movement in the mid-1960s as a story of progress toward greater inclusiveness and equality. Hinton’s sweeping narrative uncovers an altogether different history, taking us on a troubling journey from Detroit in 1967 and Miami in 1980 to Los Angeles in 1992 and beyond to chart the persistence of structural racism and one of its primary consequences, the so-called urban riot. Hinton offers a critical corrective: the word riot was nothing less than a racist trope applied to events that can only be properly understood as rebellions―explosions of collective resistance to an unequal and violent order. As she suggests, if rebellion and the conditions that precipitated it never disappeared, the optimistic story of a post–Jim Crow United States no longer holds.

Black rebellion, America on Fire powerfully illustrates, was born in response to poverty and exclusion, but almost immediately in reaction to police violence. In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson launched the “War on Crime,” sending militarized police forces into impoverished Black neighborhoods. Facing increasing surveillance and brutality, residents threw rocks and Molotov cocktails at officers, plundered local businesses, and vandalized exploitative institutions. Hinton draws on exclusive sources to uncover a previously hidden geography of violence in smaller American cities, from York, Pennsylvania, to Cairo, Illinois, to Stockton, California.

The central lesson from these eruptions―that police violence invariably leads to community violence―continues to escape policymakers, who respond by further criminalizing entire groups instead of addressing underlying socioeconomic causes. The results are the hugely expanded policing and prison regimes that shape the lives of so many Americans today. Presenting a new framework for understanding our nation’s enduring strife, America on Fire is also a warning: rebellions will surely continue unless police are no longer called on to manage the consequences of dismal conditions beyond their control, and until an oppressive system is finally remade on the principles of justice and equality.

In “America on Fire,” the historian Elizabeth Hinton offers a sweeping reconsideration of the racial unrest that shook American cities in the 1960s and 70s.

Elizabeth Hinton wants history to help break cycles of police violence. “We’re never going to get out of this until we understand how we got here.”

For her first book, “From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime,” the historian Elizabeth Hinton spent years digging through government archives, piecing together how bipartisan tough-on-crime federal legislation had funded an expansion of policing and set the stage for the mass incarceration we live with today.

She had been pursuing a classic directive — follow the money. But shortly after she finished the book, a chance conversation set her archival antennae quivering in a different way.

At a backyard barbecue, she met a political scientist who mentioned he had the archives of the Lemberg Center for the Study of Violence, a short-lived enterprise founded in 1965. Soon she found herself sorting through box after box of newspaper clippings documenting the racial disturbances across the country in the years that followed.

There were reports from the famous uprisings that rocked Watts, Newark, Detroit and other urban centers, including more than 100 that erupted after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968. But there were also articles documenting disturbances stretching well into the early ’70s, in Greensboro, N.C.; Sylvester, Ga.; Ocala, Fla.; York, Penn.; Waterloo, Iowa, and hundreds of other smaller cities and towns — events that had all but fallen out of public memory.

“It was just story after story after story after story, It was fascinating to see them come alive.”

Now, in a new book, “America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s,” Hinton offers a sweeping account of the turmoil. From May 1968 to December 1972, by her count, some 960 Black communities across the country saw 1,949 separate disturbances, resulting in nearly 40,000 arrests, with more than 10,000 people injured and at least 220 killed.

These incidents, which were often violent, were labeled “riots,” a label which has stuck, including in the scholarship. But Hinton argues that they must be understood as “rebellions” — part of a “sustained insurgency” against entrenched inequality and the harsh policing of the escalating war on crime.Students at De La Warr High School in New Castle, Del., on Sept. 24, 1969. De La Warr was one of a number of schools that saw student rebellions in those years, according to Hinton’s “America on Fire.”

It’s a lost chapter of history, she argues, but also one that’s crucial to understanding the mass protests against police violence in our own time, from Ferguson, Mo., in 2014 to seemingly everywhere in 2020 after the police killing of George Floyd.

“We are still living in the aftershocks of this period,” Hinton said. “The threat of Black rebellion,” she added, “is a key to understanding U.S. history, but especially to understanding the post-civil rights period, and how we get to mass incarceration.”

“America on Fire,” comes trailing enthusiastic endorsements from a raft of prominent scholars, including Henry Louis Gates Jr., Jill Lepore and Eric Foner. It’s a mark both of the book’s timeliness, and Hinton’s stature as a rising star in a historical profession that is increasingly seeking to understand the explosive growth of the carceral state.Hinton drew on sources like “On the Battlefront,” a pamphlet by the United Front, a Black community group founded in Cairo, Ill., in the late 1960s to defend against white vigilantes.Credit…Ike Abakah for The New York Times

A decade ago, carceral history felt like “a few of us working in a basement,” said Heather Ann Thompson, a longtime friend and mentor to Hinton and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy.” Today, it’s a buzzing subfield, in which Hinton’s work, Thompson said, stands as “canonical.”

“Her first book really showed us where the punitive police apparatus came from,” she said. “Here, she shows us the importance and power of resistance.”

Hinton, 37, grew up in Ann Arbor, Mich. Her father, Alfred Hinton, is a retired art professor. Her mother, Ann Pearlman, is a therapist and writer.

As a child, she loved hearing stories about her father’s family, who arrived in Saginaw, Mich., during the Great Migration and became autoworkers. And she was fascinated by the history of Inkster, a declining town near Detroit where Henry Ford had set up what she called a system of “urban sharecropping” for his Black employees (and which later became the site of one of the rebellions recounted in “America on Fire”).

“It sounds corny, but history was always part of who I am,” she said.

So was questioning racism and injustice. In high school, she wrote a paper arguing that slave rebellions were justified under the ideas of the Declaration of Independence (an argument echoed in the introduction to “America on Fire”). For another paper, which challenged the stereotype of Black people as inherently violent, she found herself debating the white supremacist David Duke.

“I challenged something horrible he wrote online, and he actually wrote back,” she said. “So I included it in my paper.”

In graduate school at Columbia, she didn’t always feel like the origin of the war on crime was a hot topic. “A lot of people thought I was crazy,” she recalled. “My Black Studies friends said, ‘Why would you want to study federal policy?’”

Then, in 2010, when Hinton was in the middle of her dissertation research, Michelle Alexander published “The New Jim Crow,” which became a surprise bestseller and helped galvanize a bipartisan reconsideration of mass incarceration. That same year, Thompson published “Why Mass Incarceration Matters,” an influential article in the Journal of American History asking why historians had largely ignored the subject, despite its vast impact on American life.

Research on mass incarceration has since exploded on American campuses, even if the activism that scholars like Hinton bring to the subject has sometimes been an uneasy fit.

At Harvard, where she taught from 2014 to 2020, she was part of a group of scholars pushing the university (so far unsuccessfully) to establish a prison education program, like those at many other institutions. She also championed the application of Michelle Jones, an incarcerated woman who was admitted to the university’s Ph.D. program in history near the end of her sentence, only to have the administration rescind the admission after some faculty members raised concerns that Jones had downplayed her crime during the application process.

Asked about that period, and her departure last year for Yale (where she has a secondary appointment in the law school), Hinton gave a long pause before speaking carefully.

“Expanding educational opportunities to people who have been systematically undereducated seem like it should be a basic goal of all educators,” she said, calling Harvard’s lack of a prison education program a “stain on the university.” (Hinton is now on the board of the Yale Prison Education Initiative, which recently received a $1.5 million grant from the Mellon Foundation.)

Hinton says that when she first encountered the Lemberg material, she saw it as countering books like Michael Javen Fortner’s recently published “Black Silent Majority,” which argued that the push for the tough-on-crime laws that ushered in mass incarceration came not just from whites, but from African-Americans concerned about growing crime and addiction in their neighborhoods.

The rebellions, she argues, add a missing layer to the story of how Black Americans — particularly the young and impoverished, whose voices are often missing from traditional archival sources — reacted to the escalation of policing.

For many, the response was “fighting back,” she said. “It was throwing rocks when police suddenly arrived to break up a house party or arrested a group of teenagers playing in a park or got involved in evicting people from housing projects.”

Hinton’s book may also heighten another fraught debate: what to call these events. Riots? Rebellions? Civil disturbances? Insurrections?

Hinton, while not downplaying the sometimes shocking violence of the events, stands firm on her preference: rebellions.

But some scholars say that term risks imposing a political coherence on events that drew a range of participants, with a range of motivations — to say nothing of Black citizens who did not participate, or saw their homes or businesses destroyed.

Michael Flamm, a historian at Ohio Wesleyan University, said that in his recent book, “In the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on Crime,” he mostly used “riot,” which was the term used most often by both African-Americans and whites at the time.

“It depends on who you see as the key actors,” he said. “Frame of reference matters. So does the politics of the scholars writing about these events.”

As part of her book, Hinton worked with Christian Davenport, a political scientist at the University of Michigan and the scholar who first showed her the Lemberg archive, to create a timeline of Black rebellions.

Davenport, who is in the process of making the Lemberg materials available online via the Radical Information Project, is also pursuing his own quantitative analysis, including looking at factors that might distinguish a “riot” from a “rebellion.” He credits Hinton’s historical approach with helping to “open this period up.”

“Her work tries to provide some kind of agency and political meaning to these folks’ actions, as opposed to the older way of thinking in terms of the madness of crowds,” he said.

The Lemberg materials stop in 1972, a year before the center (which was housed at Brandeis University) closed. But in the book, Hinton also flashes forward to later eruptions in Miami in 1980, Los Angeles in 1992, and Cincinnati in 2001 — “aftershocks” of the rebellion period, she writes, that were precipitated by police officers killing or brutalizing Black men.

As for the Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, Baltimore, Minneapolis and elsewhere, she is careful, she notes, not to describe them as “rebellions.”

Unlike the earlier unrest, “they all started out as peaceful protests,” she said. “Once the police came in with tear gas, that sometimes led to burning and looting and throwing water bottles at the police. But they all started peacefully.”

As the one-year anniversary of the outcry over George Floyd’s killing approaches, she said she hoped her work will not just illuminate the past, but help change the future.

“This history is an attempt to break-up cycles,” she said. “We’re never going to get out of this until we understand how we got here.”