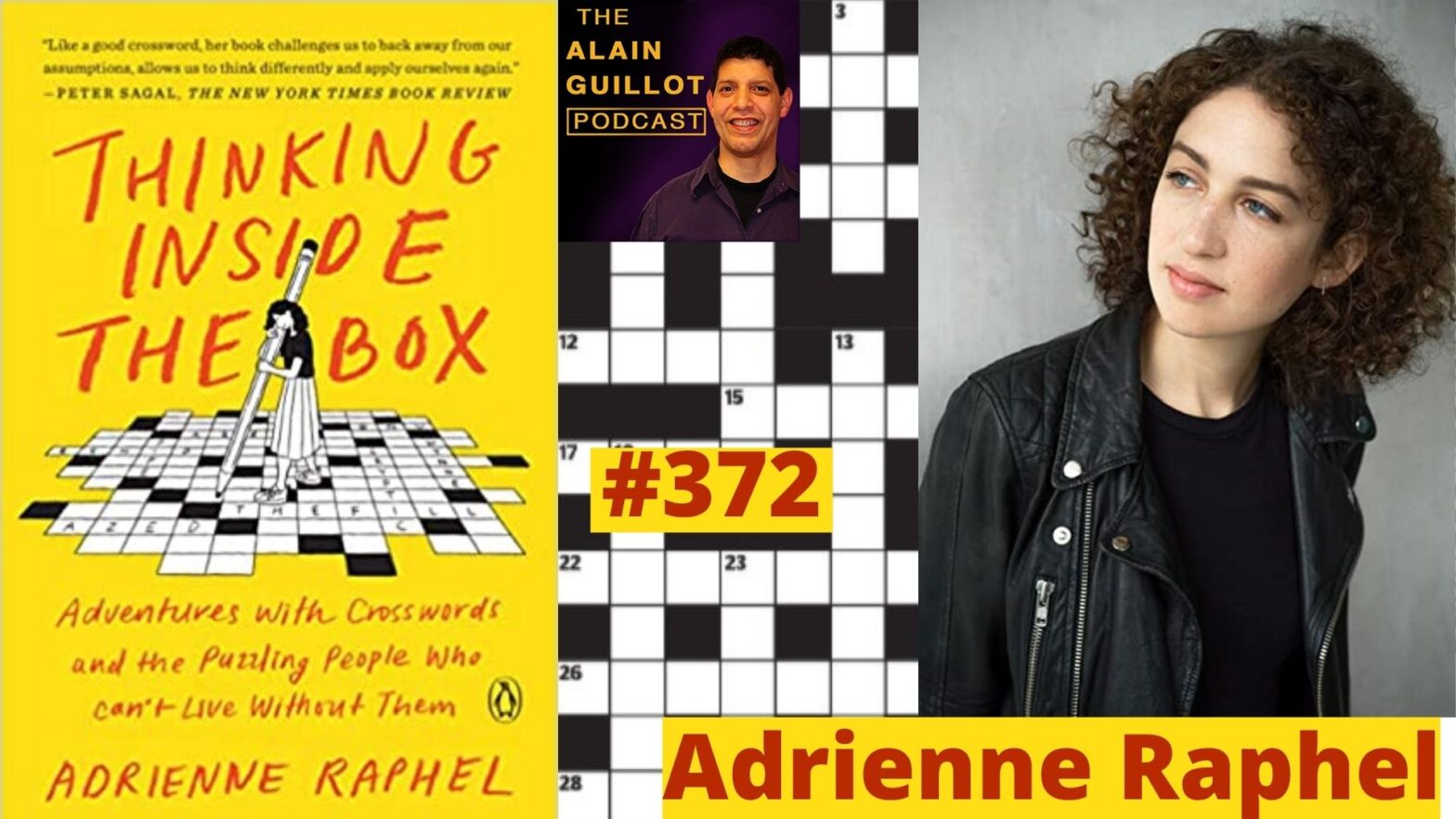

About Adrienne Raphel

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them,

and What Was It For. Her essays, poetry, and criticism appear in The New Yorker, Poetry, The New Republic, The Atlantic, Paris Review Daily, Slate, Lana Turner Journal, Poets & Writers, The Iowa Review, and other publications.

Born in New Jersey and raised in Vermont, Raphel holds a PhD in English from Harvard University, an MFA in poetry from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and an AB (summa cum laude) from Princeton University. She is currently a Lecturer in the Princeton Writing Program.

Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them

Almost as soon as it appeared, the crossword puzzle became indispensable to our lives.

Invented practically by accident in 1913, when a newspaper editor at the New York World was casting around for something to fill empty column space, it became a roaring commercial success almost overnight. Ever since then, the humble puzzle has been an essential ingredient of any newspaper worth its salt. But why, exactly, are the crossword’s satisfaction so sweet?

Blending first-person reporting from the world of crosswords with a delightful telling of its rich literary history, Adrienne Raphel dives into the secrets of this classic pastime. Thinking Inside the Box is an ingenious love letter not just to the abiding power of the crossword but to the infinite joys and playful possibilities of language itself.

In a 1924 editorial headlined “A Familiar Form of Madness,” this newspaper expressed its disdain for that vulgar new entertainment, that lowly diversion for idle minds, that pointless display of erudition known as the “cross-word”: “Scarcely recovered from the form of temporary madness that made so many people pay enormous prices for mahjong sets, about the same persons now are committing the same sinful waste in the utterly futile finding of words the letter of which will fit into a prearranged pattern, more or less complex.” A year later, this Olympian condescension had gotten a little desperate: “The craze evidently is dying out fast and in a few months it will be forgotten.”

How and why this “craze” arose and persisted, and how The New York Times came to not only change its institutional opinion but become the epicenter of American crossword culture, is the story told by Adrienne Raphel in her cultural and personal history of crosswords and the “puzzling people who can’t live without them,” of which she is clearly one. At the end of this diverting, informative, and discursive book, her love for crosswords is clear, but her reasons — despite a determined effort on her part to explain them — remain, in the end, a puzzle of their own.

Raphel proves a skilled cultural historian, dipping into newspaper archives and movie reels and private correspondence to describe how the crossword came to conquer the world. The first “Word-Cross Puzzle” was invented out of desperation by Arthur Wynne, the British-born editor of the Sunday color supplement (titled, simply, “FUN”) for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. The deadline for the Christmas 1913 edition was upon him, and he had a blank space and nothing to fill it with. Perhaps that very problem suggested its solution: a puzzle in which readers had to fill in blank spaces with ideas of their own.

That first puzzle was in the shape of a diamond, or perhaps as close to a Christmas wreath as the graphics of the time could provide. The clues were straightforward — “What we should all be” yielded the answer “MORAL” — but the essential idea of a modern crossword, an interlocked array of words in which each solution provides clues to the next, was there. Wynne built his work, as Raphel describes, on centuries of wordplay and word squares, in which words could be read across and down a grid of letters. Wynne wanted to patent his creation, but The New York World refused to pay for the application — thus saving themselves almost $100.

The paper may have come to regret that, as the crossword instantly became the most popular feature in FUN, if not the entire World. Wynne became overwhelmed with the demand for more and better puzzles and eventually foisted the whole thing off onto his secretary, Margaret Petherbridge, a refined graduate of Smith College. At first Petherbridge, like The Times, thought it a diversion beneath her talents: a snobbery that ended when she tried to solve one herself. Suddenly she understood why “what had seemed like a major nuisance could be her chance to make her mark. … Placing her left hand on a dictionary and raising her right, Petherbridge vowed to take up the crossword.”

It was Petherbridge who established the essential elements of modern crosswords: the rigorous proofreading, the separate lists of Across and Down clues, the avoidance of “unchecked boxes,” or squares that were only part of a single word. As such, she became the true parent of the crossword. Wynne may have birthed it, but Petherbridge raised it.

Raphel starts her book with the bold thesis “It’s hard to imagine modern life without the crossword” and the closest she comes to proving it is during those early decades, when crosswords were the basis for comic strips — “Cross Word Cal,” by Ernie Bushmiller (who went on to create “Nancy,” itself a bit of a puzzle) — murder mysteries, even a 1925 Disney short, “Alice Solves the Puzzle.” In April 1925 the new magazine The New Yorker profiled a comely 20-year-old Wellesley dropout named Ruth von Phul, the winner of the inaugural Herald Tribune National All Comers Cross Word Puzzle Tournament. Raphel describes the delight of the unnamed reporter, disabused of the assumption that “someone who is freakishly good at crosswords will, of course, be male, be socially awkward and have a face made for radio.” I feel seen.

In the end, it took the attack on Pearl Harbor to persuade The Times to abandon its sneer. Margaret Petherbridge — now Margaret Farrar, after marrying the co-founder of the famed publishing house Farrar, Straus & Giroux — wrote to The Times’s publisher, Arthur Hays Sulzberger: “I don’t think I have to sell you on the increased demand for this type of pastime in an increasingly worried world. You can’t think of your troubles while solving a crossword.” Farrar became the paper’s first crossword puzzle editor, the founding dynasty of the Hapsburgs of the crossword empire.

It is in the modern era that this book loses its lapidary elegance. Raphel profiles some of the pastime’s modern titans, including the reigning monarch Will Shortz, current Times puzzle editor (and NPR “puzzle master”). We meet many constructors and their artful creations, and we visit the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, founded by Shortz and held each spring in Stamford, Conn. But none of these people seem as vivid as their long-dead predecessors.

Raphel relates how Ruth von Phul, that first tournament champion, eventually set puzzles aside to become a world-renowned scholar, enamored of James Joyce’s wordplay. Or consider the romantic, elegiac chapter in which Raphel describes how Vladimir Nabokov maintained his connection to his wife, Vera, then a patient in a sanitarium, by sending her love notes filled with crosswords to solve, revealing his devotion letter by letter. But no one now alive seems quite as, well, alive.

Raphel includes a few quotes from the blog of Prof. Michael Sharp, who posts often savage reviews of every daily Times crossword under the pseudonym Rex Parker — but she never talks to him about his obsession or his adopted persona as the curmudgeonly scold whom every constructor resents but many secretly want to please. Raphel herself competes in the crossword tournament (she does poorly), but the winners go unnamed and unquoted. Who are these people, who have devoted their efforts to become the greatest crossword solvers in America? If Raphel had talked to the tournament announcer Greg Pliska, she would have discovered he’s a talented constructor who wooed his wife with a series of original puzzles, the final one of which was a crossword with the solution: “WILL YOU MARRY ME?” Perhaps not as elegiac as Nabokov — but unlike Nabokov, he’s still here.

Instead of solvers, Raphel gives us philosophy, in a chapter on representation and reality in crosswords that begins to feel stretched. Some of her assertions seem disproportionate, as when she claims: “We tell ourselves games in order to live.” (Somewhere, Abraham Maslow mutters, “Really?”) I am a philistine, socially awkward with a face made for radio, but I would rather associate myself with the less cerebral explanation offered by Thomas Harris, in a very different context, in his novel “The Silence of the Lambs”: “Problem-solving is hunting; it is savage pleasure and we are born to it.”

In my favorite memoir chapter, Raphel visits a writing retreat to constructing her own crossword. After much technical discussion of grids and themes and fill, she writes: “I became a mechanical god. I shifted gears; I tuned each letter individually. … I was a chemist, titrating my micro-universe; a lepidopterist, shifting a butterfly’s wing onto a pin.” She was also, in this and only this, a failure. Her puzzle was rejected, as so many are, by The Times. But her affectionate exegesis of this pastime, this passion, this “temporary madness,” succeeds. Like a good crossword, her book challenges us to back away from our assumptions, allows us to think differently, and apply ourselves again.